When you hear mention of the Orkney islands, off Scotland’s northeast coast, what do you think of?

When you hear mention of the Orkney islands, off Scotland’s northeast coast, what do you think of?

For me, they conjure up a northern vision of Orkneymen, the founding of the Hudson’s Bay Co. on May 2, 1670 (I still recall this date after wearing hundreds of HBC clothing labels over the decades), the Arctic expansion of the Canadian fur trade, and Dr. John Rae, who found the final portion of the Northwest Passage and discovered the ultimate fate of the Franklin Expedition (1846-47).

All of the above entered my consciousness at the Arctic Institute of North America at the University of Calgary, over many spirited discussions with board members and research associates when I was executive director.

The likes of Tom Beck, James Raffan, Ernie Pallister, Dr. Joan Ryan and Ethel Blondin-Andrew were all contributors to my early store of Orkney lore. They helped me define a form of northern mythology associated with these islands and the contribution they made to the Arctic culture that’s so much a part of our national identity. From their first mention, I began cultivating a desire to visit.

Last week, my wife and I finally made it to their shores. We went with my sisters and a group of friends as part of a family trip of discovery to Caithness and Sutherland, the old Highland territories that define the very northern tip of Scotland. From Inverness, we drove to Bighouse Lodge, Melvich in Sutherland, and from there to the ferry port at Scrabster near Thurso. Just keeping the place names clear in our heads was a delight.

The next step in our Orkney pilgrimage involved boarding the breakfast sailing of the MV Hamnavoe (the old Norse name for Stromness) for Stromness, the second-most populated Orkney town. The 50-km crossing took place in rolling seas and a defining mist. The island of Hoy first came into view, and we thrilled to a high seastack (a rock tower) called the Old Man of Hoy jutting from its southwest corner.

Stromness is on Mainland, the largest Orkney Island, just north of Hoy. It’s home to just over 17,000 of the approximately 21,000 Orkney residents.

As Stromness loomed dockside upon our arrival, it immediately evoked memories of St. John’s and Petty Harbour, in Newfoundland. The only difference is the stone-wall construction (rather than milled timber) of the housing stock.

We walked off the Hamnavoe to a waiting mini tour bus, immediately feeling a sense of self-contained cultural assurance. The accents of our fellow Orkney travellers and their waiting friends and family were markedly different from Caithness. The children walking and biking to school were blonde and blue-eyed. The fishing fleet tied up at the walled inner harbour was comprised of no-nonsense North Sea vessels. It all channelled a kind of subtle Norse air.

Patricia Long, our guide with About Orkney tours, welcomed us aboard the bus with the news that Skara Brae would be our first destination. It was described as the oldest (at 5,000 years) Neolithic (the archaeological era heralding agriculture) site in western Europe.

We soon arrived at a broad sandy bay north of Stromness. The site featured an excellent interpretive centre and a reconstructed stone-walled family residence that we were able to stroll about and touch and sense.

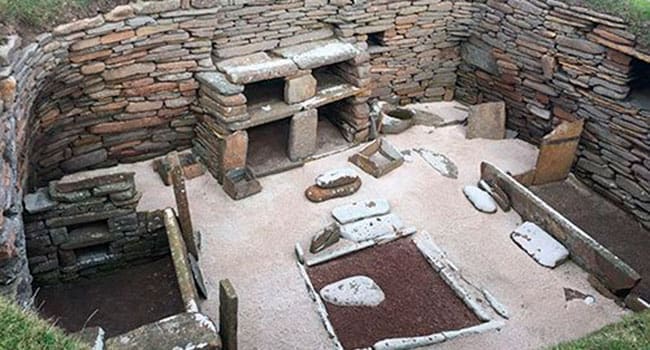

Then we were released for an archaeological walk-about, looking down into the real surviving houses from a paved pathway. The houses nested almost bird-like, adjacent to one another. All featured a central living chamber with walled stone beds, a central fire pit, and an altar-like ‘stone dresser’ to hold food and cooking implements. The floors were lined with paving slabs and the walls were made of stone cobbles that fit tightly together.

The roofs were all open. We were told that they were originally timbered and thatched, but this organic material had long since rotted away and fallen into the houses.

After Skara Brae, we were bused to the Standing Stones of Stenness. This is another Neolithic construction, just a few kilometres from Skara Brae. Four of the ring’s defining stones still stand. The tallest reaches over six metres. Archaeologists estimate the ring originally contained 12 megaliths. And they speculate the site had a function similar to Stonehenge.

Mike Robinson has been CEO of three Canadian NGOs: the Arctic Institute of North America, the Glenbow Museum and the Bill Reid Gallery. Mike has chaired the national boards of Friends of the Earth, the David Suzuki Foundation, and the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society. In 2004, he became a Member of the Order of Canada.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.