Hugh Hefner’s death has resulted in Latin maxims battling in my head. On one hand, “De mortuis nil nisi bonum” (“Of the dead say nothing but good”) is wise and charitable. But so too is “De mortuis nil nisi verum” (“Of the dead speak nothing but the truth”).

Hugh Hefner’s death has resulted in Latin maxims battling in my head. On one hand, “De mortuis nil nisi bonum” (“Of the dead say nothing but good”) is wise and charitable. But so too is “De mortuis nil nisi verum” (“Of the dead speak nothing but the truth”).

If we spoke nothing but the truth about the man, we would find very little good to say. So I’ll chart a middle course in assessing the impact of his 91 years on this planet.

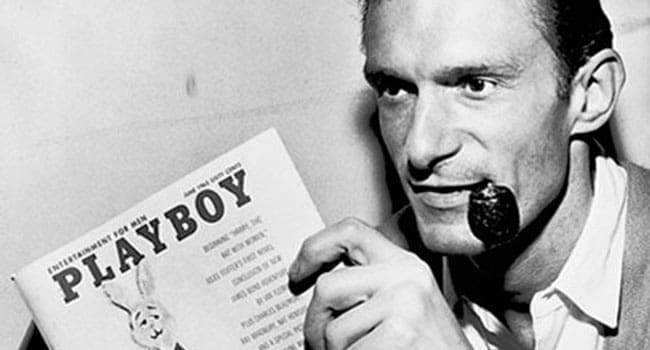

Hefner was a brilliant entrepreneur.

In 1953, using borrowed money, he assembled a nude photo of Marilyn Monroe purchased from a photo agency, pieces of fiction lifted from Giovanni Boccaccio, Ambrose Bierce and Arthur Conan Doyle (all long dead and unlikely to sue for payment), a chicken-and-rice recipe, a football piece with free pictures supplied by the University of Illinois’ sports department, a look at the Dorsey brothers that wondered if they would revive swing music, an article on the high cost of divorce and some cartoons, and published it as the first issue of Playboy magazine.

It was cheap but pretentious and self-consciously urban-sophisticate. It was, said Hefner in his introductory column, “a pleasure primer for the masculine taste” but it was not the typical men’s outdoor magazine.

“We plan on spending most of our time inside,” said Hefner. “We like our apartment. We enjoy mixing up cocktails and an hors d’oeuvre or two, putting a little mood music on the phonograph and inviting in a female acquaintance for a quiet discussion on Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, sex.”

It was the start of something big: a publishing empire based on smut.

Until Hefner came along, pornographic images were sold furtively or watched in flickering eight-mm in smoky basements of men’s clubs. Hefner commodified bare breasts for a mass market. His mixture of lewd pictures with ads for high-end stereos and cars, sprinkled with progressive politics, made Playboy wildly popular with two generations of young men who learned, as they said, to read with one hand.

Along with the inventors of the contraceptive pill, Hefner advanced a social revolution by proposing the impossible: sex without responsibility.

Enter Harvey Weinstein, for few men embody the Hefner approach to sex as well as the now-disgraced movie producer. For Weinstein, women appear to have been commodities, to be enjoyed whenever and wherever his pleasure demanded.

Despite being overweight and slovenly, Weinstein apparently had his way with beautiful actresses. For decades, they kept silent because of the power he wielded in Hollywood, in an industry that leads the way in selling sex and violence as entertainment.

Hefner died a tawdry parody of his former self but society is still paying the price for his program. He taught North American males that sexual pleasure should be unrestrained by morality or consequence; his philosophy drastically lowered the cost of copulation.

Before Hefner and the pill, the price males generally paid for sex was marriage or at least signals of emotional commitment. After Hefner and his disciples (including Weinstein), the price was low for the individual male but extremely high for society: epidemics of sexually-transmitted diseases, high rates of single-woman pregnancy, family breakup, porn addiction, and a crisis in the relationship between men and women that is far from resolved.

Rest in peace, Hefner. We’re still cleaning up after you.

And Weinstein: get some professional help.

Gerry Bowler is a Winnipeg historian and a senior fellow at the think-tank Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Gerry is a Troy Media Thought Leader. Why aren’t you?

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.